A New Dawn: The SHANTI Bill and India's Nuclear Renaissance

A New Dawn: The SHANTI Bill and India's Nuclear Renaissance

The Union Cabinet's approval of the Sustainable Harnessing of Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India (SHANTI) Bill, 2025, marks the most consequential legislative and policy shift in India’s civil nuclear sector since the dawn of the atomic age in 1962. Branded as a monumental reform, the SHANTI Bill signals a decisive transition from a tightly controlled, state-dominated framework to a modern, investment-friendly, and safety-centric regime. This pivotal move is not merely an administrative update; it is an explicit strategic choice to position nuclear energy as the cornerstone of India’s long-term energy security, industrial growth, and ambitious net-zero emissions target by 2070. The Bill’s comprehensive nature, replacing fragmented, decades-old laws, is set to unlock unprecedented private and global capital, which is crucial for achieving India's staggering goal of 100 GW of nuclear power capacity by 2047.

Dismantling the Sixty-Year-Old State Monopoly

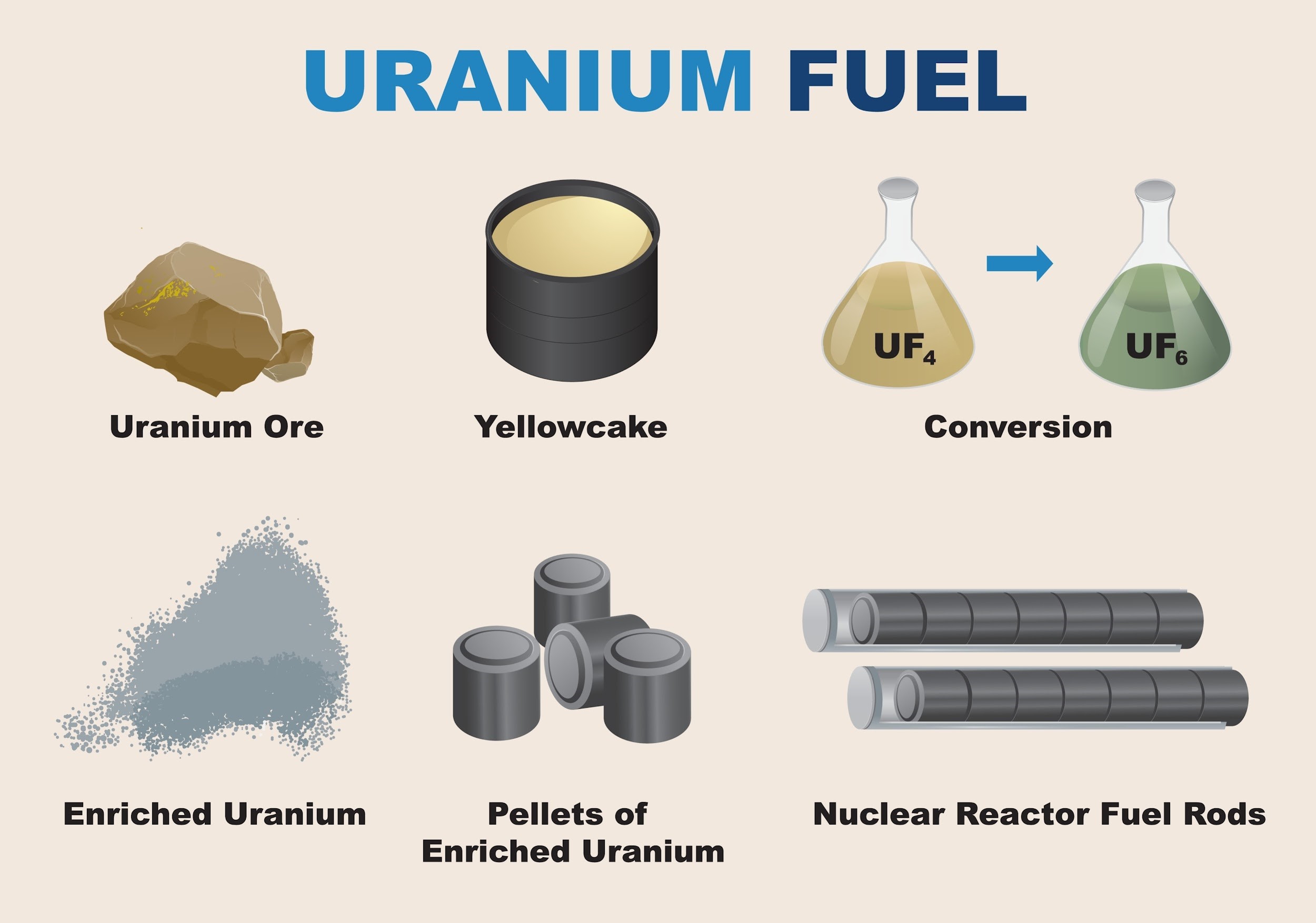

The fundamental purpose of the SHANTI Bill is to dismantle the strict state monopoly established by the Atomic Energy Act, 1962. For over six decades, the law strictly prohibited private entities from operating nuclear power plants, limiting capacity addition and restricting the entire nuclear value chain, from atomic mineral exploration (like uranium and thorium) to power generation, to the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) and its public sector undertaking, the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited (NPCIL).

This highly restrictive model, while ensuring strategic autonomy and safety oversight, has severely constrained the pace of expansion. The SHANTI Bill proposes to transform this structure by enabling private sector entry into the non-strategic parts of the value chain, such as equipment manufacturing, auxiliary services, and fuel fabrication. It allows for private companies to take up to 49% minority equity in nuclear power generation projects, paving the way for public-private partnerships and joint ventures. This infusion of private capital and operational efficiency is indispensable for scaling up capacity ten-fold in two decades, a task deemed impossible for the public exchequer alone. The core strategic functions specifically, the production of special nuclear materials, heavy water, and radioactive waste disposal will, however, remain under exclusive DAE control, ensuring national security safeguards are preserved.

Reforming the Nuclear Liability Architecture

A critical deterrent for foreign vendors and domestic private investors has been the ambiguous and heavy liability framework under the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act, 2010 (CLND Act). This Act, particularly its Section 17(b), which granted the operator a 'right of recourse' against the supplier for faulty equipment or services, was a major sticking point, effectively stalling commercial nuclear collaborations.

The SHANTI Bill directly addresses this issue by proposing a reformed nuclear liability architecture that aligns with global norms, specifically those of the International Atomic Energy Agency’s Convention on Supplementary Compensation (CSC). Key features of this reform include a clearer delineation of operator-supplier responsibilities and the introduction of insurance-backed liability caps. The maximum liability for each nuclear incident shall be the rupee equivalent of three hundred million Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) or a higher amount determined by the Central Government, with the government providing a sovereign backstop for compensation beyond a defined threshold. This financial clarity and risk-mitigation mechanism are expected to restore investor confidence and unlock technology transfer from global nuclear power firms.

Establishing an Independent Nuclear Safety Authority

Trust and transparency are paramount in the nuclear domain. The current regulatory environment, where the safety oversight body, the Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB), operates under the administrative control of the DAE, is often criticised for its lack of complete structural independence. The SHANTI Bill commits to creating a new, Independent Nuclear Safety Authority.

This new regulator will be statutorily independent, professional, and mandated to ensure transparent, globally benchmarked safety oversight, rigorous licensing, compliance monitoring, and enforcement across the entire nuclear value chain. Separating the roles of promoter (DAE) and regulator (the new Authority) enhances institutional integrity, aligns India with international best practices (like those adopted by the US NRC), and is crucial for building public confidence, a prerequisite for any large-scale nuclear expansion, particularly involving new technologies and private participation.

Driving Innovation: The Small Modular Reactor (SMR) Push

Recognising the shift towards more flexible, safer, and quicker-to-deploy nuclear technologies, the SHANTI Bill strongly supports the research, development, and deployment of Small Modular Reactors (SMRs). SMRs, which are advanced reactors typically having a generating capacity of less than 300 MWe, are poised to be a game-changer for India's decarbonisation strategy.

These smaller, factory-built, and scalable units are ideal for decentralised deployment, providing stable, baseload power for critical applications like hydrogen production, seawater desalination, and crucially, the rapidly expanding industrial parks and data centres. The government’s Nuclear Energy Mission, announced alongside the Bill, backs this focus with a substantial outlay of dedicated funding for SMR R&D, with a target to operationalise at least five indigenous SMRs by 2033. The Bill’s framework aims to attract private sector expertise and capital to accelerate the development and commercialisation of this new technology pillar.

Streamlining Governance and Dispute Resolution

To facilitate a smooth and efficient transition to this new liberalised sector, the SHANTI Bill consolidates the multitude of outdated and fragmented laws into a Unified Legal Framework for licensing, safety, compliance, and operations. This simplification is intended to reduce red tape and regulatory ambiguity, making the sector more attractive to business and drastically cutting project timelines. The Bill proposes to repeal the Atomic Energy Act, 1962, and the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act, 2010.

Furthermore, the Bill proposes the establishment of a Dedicated Nuclear Tribunal. This specialised mechanism will be empowered to handle the efficient settlement of liability, contractual breaches, and other disputes related to the civil nuclear sector. A specialised judicial body is essential to handle the high technical complexities and significant financial stakes of nuclear projects, ensuring quick and expert resolution that is critical for long-term project viability and investor assurance.

Nuclear Energy as the Linchpin of Net-Zero by 2070

The SHANTI Bill is a direct response to India's energy trilemma: the need for energy security, affordability, and climate action. As India pursues its net-zero emissions goal by 2070 and the vision of a Viksit Bharat (Developed India) by 2047, the role of nuclear power is non-negotiable.

While solar and wind are expanding rapidly, their intermittency poses a significant threat to large-scale grid stability, necessitating a reliable baseload power source that is carbon-free. Nuclear energy, being a low-carbon, high-density, and 24/7 source (with a Capacity Factor often exceeding 90%), perfectly complements the variable nature of renewables. Achieving the 100 GW nuclear target by 2047 is paramount for meeting India's projected massive electricity demand growth without compromising climate commitments or economic stability. The SHANTI Bill provides the legal and financial scaffolding to build this critical clean energy capacity.

Conclusion: Ushering in India's Nuclear Renaissance

The SHANTI Bill, 2025, represents a brave and necessary strategic gamble, transcending mere legislative amendment to become an economic, technological, and climate policy instrument. By systematically dismantling the state monopoly, modernising a flawed liability regime, strengthening safety oversight, and promoting next-generation technologies like SMRs, the Bill lays a solid foundation for India’s nuclear renaissance. The successful implementation of these reforms, particularly in attracting sophisticated foreign and domestic private capital under robust regulatory checks, will determine if nuclear energy can indeed evolve from a niche contributor into a central pillar of India’s energy future, powering its aspirations for economic development and climate leadership on the global stage.