Decline of Indus Valley Civilisation

12.12.2025

Decline of Indus Valley Civilisation

Context

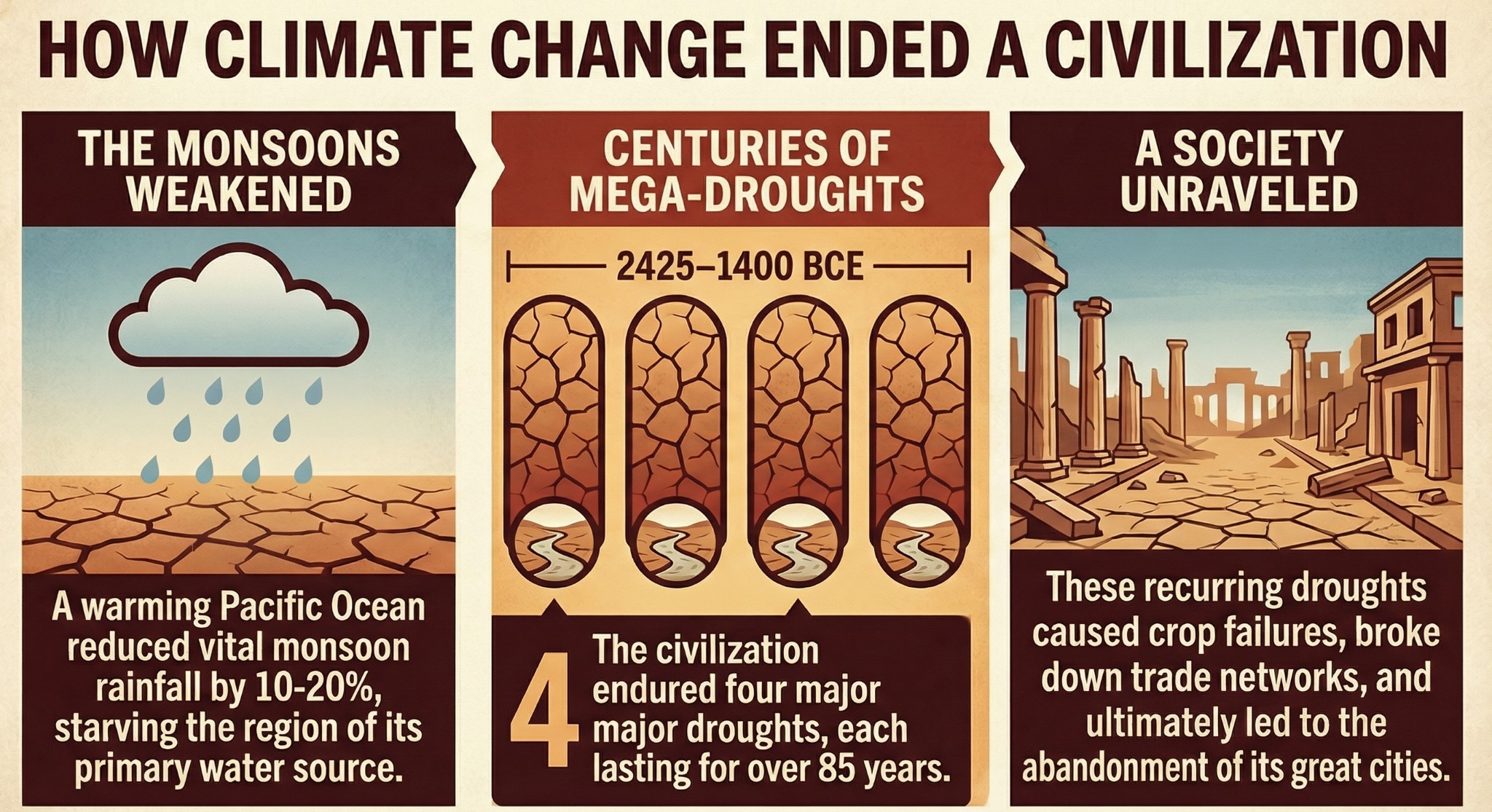

A new multi-proxy paleoclimate study has claimed that the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) declined due to centuries-long recurring droughts, not a single catastrophic event.

About Decline of Indus Valley Civilisation

What it is?

- The Indus Valley Civilisation (3300–1300 BCE), also called Harappan Civilisation, was one of the world’s earliest urban cultures spread across present-day Pakistan and northwest India.

- It originated along the Indus and Ghaggar-Hakra (Sarasvati) river systems, evolving into a sophisticated Bronze Age civilisation known for cities like Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro, Rakhigarhi, and Dholavira.

Features of Indus Valley Civilisation

- Art & Craft: Highly developed craftsmanship in bead-making, pottery, terracotta figurines, shell–copper–bronze artefacts, and the iconic “Dancing Girl” and “Priest-King” sculptures.

- Architecture & Urban Planning: World-class urban design with grid-pattern streets, multi-storey brick houses, citadels, granaries, and advanced drainage with covered sewerage and soak pits.

- Script & Literature: Used a still-undeciphered pictographic script found on seals, tablets, and pottery; no surviving textual literature, but inscriptions show a complex symbolic system.

- Economy: A diversified economy based on agriculture (wheat, barley, cotton), craft industries, internal trade, and long-distance trade with Mesopotamia, Oman, and Iran (evident from seals, weights, and boats).

- Society & Governance: Urban society with standardised weights, uniform architecture, and planned layouts, implying an efficient civic authority; evidence suggests a largely peaceful, egalitarian society with little social stratification.

Decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation

New Evidence from 2025 Study

- Decline was gradual, triggered by four major mega-droughts (2425–1400 BCE):

- The study identifies four prolonged drought phases, each lasting over 85 years, with the most severe one peaking around 1733 BCE for nearly 164 years.

- These droughts did not occur once but in cycles, creating centuries of hydrological instability, which progressively weakened agriculture, trade, and urban functioning.

- Weakening monsoons due to warming of the tropical Pacific:

- Climate records show that the tropical Pacific shifted from a cool, La Niña-like phase (3000–2500 BCE) to a warmer, El Niño-like phase.

- This directly reduced monsoon rainfall by 10–20%, drastically lowering water availability for fields, reservoirs, and rivers.

- Hydrological changes: rivers shrank and soils dried up:

- The study combines lake cores, cave stalagmites, and climate models to show that rivers like the Sutlej-Ghaggar system, Beas, and many tributaries experienced reduced flows.

- Soil moisture declined, leading to desiccation, salinity build-up, and reduced crop yields — especially in areas away from the Indus River.

- Impact on agriculture and food systems:

- Crop failures increased, forcing Harappans to shift from water-intensive crops (wheat, barley) to drought-resistant ones like millets.

- Agricultural stress weakened the surplus system that supported large urban centres.

- Breakdown of long-distance trade and economic networks:

- Lower river levels made river navigation difficult, reducing connectivity to Mesopotamia, the primary trade partner.

- Reduced rainfall and shrinking lakes also made overland routes riskier.

- This decline in external trade undermined urban jobs (bead makers, potters, metalworkers), destabilising the economic base.

Other Classical Theories

- Changes in River Systems (Indus & Ghaggar-Hakra shifts):

- Tectonic movement altered the courses of key rivers.

- The Ghaggar-Hakra (Sarasvati) dried gradually, leading to the abandonment of major settlements like Kalibangan and Banawali.

- The Indus River occasionally flooded massively, depositing silt and destroying fields, while later shifting away from some cities.

- Collapse of Mesopotamian Trade Network:

- Around 2000 BCE, Mesopotamia faced internal political turmoil (Akkadian collapse, Ur III decline).

- As Mesopotamian trade weakened, demand for Harappan goods (beads, cotton textiles, metals) fell sharply.

- Reduced trade cut off a crucial economic pillar of urban Harappan life, contributing to industrial decline.

- Urban Overcrowding and Declining Civic Maintenance:

- Archaeology shows that many cities became densely crowded, with houses built over older streets and structures.

- The once-pristine drainage systems became clogged and poorly maintained, signalling administrative weakening.

- Public buildings like the Great Bath were built over or lost importance.

- No Evidence of Large-Scale Invasion or Warfare:

- Earlier theories proposed “Aryan invasion” based on Rig Veda references, but archaeology contradicts this:

- No mass graves indicating war.

- No burnt cities or weapons of destruction.

- Harappan society overall shows little militarisation.

- Most scholars now agree that invasion did not cause the collapse.

- Earlier theories proposed “Aryan invasion” based on Rig Veda references, but archaeology contradicts this:

Significance of Indus Valley Civilisation

- Gave India its first planned cities, sanitation systems, and urban governance models.

- Demonstrated advanced hydrology, craft specialisation, maritime trade, and agricultural adaptation.

- Offers lessons for today on water management, climate resilience, and decentralised settlement planning.

- Its peaceful culture and standardised systems highlight early forms of civil administration, trade regulation, and environmental adaptation.

Conclusion

The new scientific findings show that the Indus collapse was not a mystery or a myth but a slow climatic tragedy worsened by fragile governance and economic stress. Yet the civilisation’s adaptability for nearly two millennia underscores its resilience and sophistication. As today’s world faces climate extremes, the Indus story serves as a powerful reminder that environmental shifts can reshape even the greatest urban cultures.