Important dimensions of Governance

Important dimensions of Governance

Many theorists defined the notion of governance of current years. It is explained by group of academicians that "Public sector governance refers to the way that the state acquires and exercises the authority to provide and manage public goods and services, including both public capacities and public accountabilities (Levy, 2007). UNDP Strategy Note on Governance for Human development described that governance is "a system of values, policies and institutions by which a society manages its economic, political and social affairs through interactions within and among the state, civil society and private sector. It is the way society organizes itself to make and implement decisions achieving mutual understanding, agreement and action. It consists of the mechanisms and processes for citizens and groups to articulate their interests, mediate their differences and exercise their legal rights and obligations. It is the rules, institutions and practices that set the limits and provide incentives for individuals, organizations and firms" (UNDP, 2007). Other professionals explained the concept of governance as distinct from government, and is the process through which various stakeholders articulate their interests, exercise their rights, and mediate their differences (Debroy, 2004).

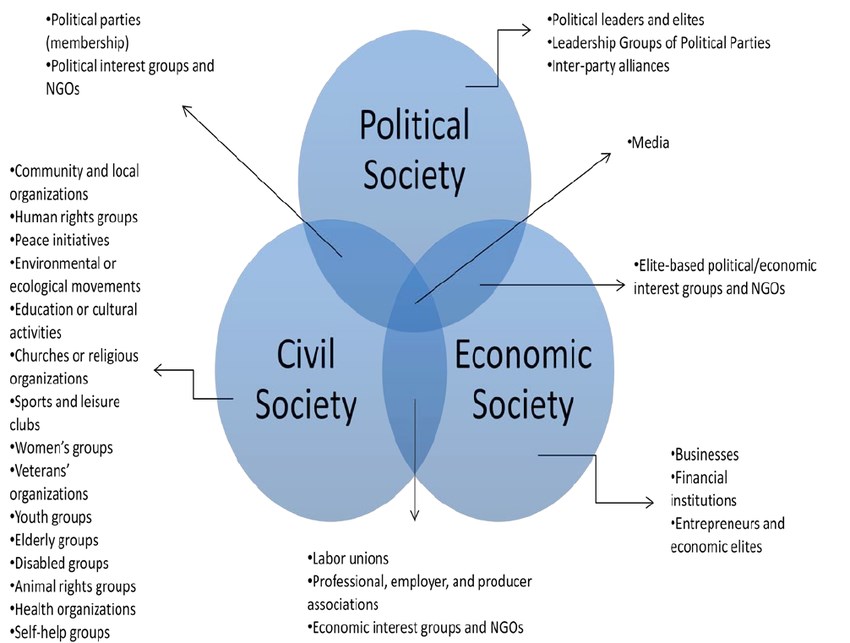

1.3 Three players of Governance:

Political Society and Governance:

Firstly it relates to the issue of establishing a durable party system. Secondly, it concerns the extent, to which elections help produce legitimate legislatures. The third refers to how well the policy aggregating function is performed by the legislature. We shall briefly discuss each one of these.

- The Party System

The role of political society, as we have indicated above, is to aggregate demands into policy. As such, it requires a manageable and functioning party system. A large number of parties are not necessarily better for how political society functions. Effectiveness is typically easier when the number is not too high. In practice, countries tend to vary according to how they strike a balance between durability and adaptability. Larry Diamond, borrowing a conceptualization from Andreas Schedler, notes that the problem in some places is an under-institutionalized party system, in others an over-institutionalized one. The more common pattern, especially in transitional societies, is one of under institutionalization. Political parties are weak and often fragmented entities, many dependent on a single charismatic individual for leadership and guidance. These parties are weak in the sense of not being able to penetrate society.

Civil Society and Governance:

Radicals, socialists, and anarchists have long advocated patterns of rule that do not require the capitalist state. Many of them look toward civil society as a site of free and spontaneous associations of citizens. Civil society offers them a non-statist site at which to reconcile the demands of community and individual freedom—a site they hope might be free of force and compulsion. The spread of the new governance has prompted them to distance their visions from that of the neoliberal rolling back of the state. Hence, the word governance is used by radicals to denote two distinct phenomena. They use it to describe new systems of force and compulsion associated with neoliberalism. And they use it to refer to alternative conceptions of a non-statist democratic order.

There is disagreement among radicals about whether the new governance has led to a decline in the power of the state. Some argue that the state has just altered the way in which it rules its citizens; it makes more use of bribes and incentives, threats to withdraw benefits, and moral exhortation. Others believe that the state has indeed lost power. Either way, radicals distinguish the new governance sharply from their visions of an expansion of democracy. In their view, if the power of the state has declined, the beneficiaries have been corporations; they associate the hollowing out of the state with the growing power of financial and industrial capital. Radical analyses of the new governance explore how globalization—or perhaps the myth of globalization—finds states and international organizations acting to promote the interests of capital.

Radicals typically associate their alternative visions of democratic governance with civil society, social movements, and active citizenship. Those who relate the new governance to globalization and a decline in state power often appeal to parallel shifts within civil society. They appeal to global civil society as a site of popular, democratic resistance to capital. Global civil society typically refers to non-governmental groups such as Amnesty International, Greenpeace, and the International Labour Organization as well as less formal networks of activists and citizens. Questions can arise, of course, as to whether these groups adequately represent their members, let alone a broader community. However, radicals often respond by emphasizing the democratic potential of civil society and the public sphere. They argue that public debate constitutes one of the main avenues by which citizens can participate in collective decision making. At times, they also place great importance on the potential of public deliberation to generate a rational consensus. No matter what doubts radicals have about contemporary civil society, their visions of democracy emphasize the desirability of transferring power from the state to citizens who would not just elect a government and then act as passive spectators but rather participate continuously in the processes of governance. The association of democratic governance with participatory and deliberative processes in civil society thus arises from radicals seeking to resist state and corporate power.

These radical ideas are not just responses to the new governance; they also help to construct aspects of it. They inspire new organizations and new activities by existing social movements. At times, they influence political agreements—perhaps most notably the international regimes and norms covering human rights and the environment. Hence, social scientists interested in social movements sometimes relate them to new national and transnational forms of resistance to state and corporate power. To some extent, these social scientists again emphasize the rise of networks. However, when social scientists study the impact of neoliberal reforms on the public sector, they focus on the cooperative relations between the state and other institutionalized organizations involved in policy making and the delivery of public services. In contrast, when social scientists study social movements, they focus on the informal links between activists concerned to contest the policies and actions of corporations, states, and international organizations.

1.6 Market and Governance:

Economic society refers to state-market relations, issues that have increasing prominence in an era of liberalization, democratization and globalization. The way states intervene to shape or reshape these rules tend to be noted by the business community and also society more generally. Such issues are important for legitimacy as well as for policy outcomes related to national development.

Three observations stand out. The first is that governance in the economic society arena can make a difference regardless of existing level of economic development and cultural orientation. The top scorers in this arena are countries with widely different backgrounds. The second point is that ex-socialist countries seem to encounter greater difficulties in this arena than those countries, which have had already for some time an exposure to a market economy. Their transition to a market economy is relatively recent and it must be acknowledged that it takes time. The third point is that most countries have made progress, including those with problems. Economic reform is paying off, even if it may be more slowly than many international advisors would like. Even if globalization and liberalization have had positive impacts on these countries, most of them continue to battle with issues that affect the business climate, in particular, and governance of the regime, in general.

There are a number of implications for researchers and practitioners. For researchers, we believe the priority is for further investigation on how informal property rights may serve as the basis for formalization and the development of a legalized property rights system. For practitioners, a key issue is to go beyond the current tendency to focus primarily on issues of efficiency in this arena and to also focus on issues of legitimacy. The findings, illustrated most topically by Russia and Argentina, highlight the damage that can be caused by an unregulated unleashing of the private sector. Our study suggests that a more comprehensive strategy of improving both state and market institutions as well as linkages between them may be a more sustainable strategy to pursue. In a similar way, more attention needs to be paid to the social implications of the new economic rules that globalization is bringing to each national economy. Although the existing liberal orthodoxy continues to be the driving force behind much of the improved governance in this arena, it needs to be sufficiently tempered so that the gains to date are not reversed by a backlash caused by hubris.