The Gradual Demise: Re-evaluating the Decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation

The Gradual Demise: Re-evaluating the Decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), or the Harappan Civilisation (3300–1300 BCE), stands as one of the world's earliest and most enigmatic urban cultures. Spanning a vast area across modern-day Pakistan and northwest India, it was a Bronze Age society renowned for its sophisticated city planning, standardised architecture, and extensive trade networks. For generations, the collapse of this magnificent culture, often described as the largest of the four ancient riverine civilizations (alongside Egypt, Mesopotamia, and China), has remained one of history's great mysteries. Traditionally, theories ranged from sudden cataclysms like mass invasions or monumental floods to internal decay. However, a significant shift has occurred in recent scholarship, spearheaded by a multi-proxy paleoclimate study. This new evidence forcefully argues that the civilization’s decline was not a sudden catastrophic event but a slow, profound process of de-urbanisation triggered by centuries-long recurring droughts and resulting hydrological instability.

The Zenith of the Harappan Civilisation

Before its decline, the Harappan Civilisation represented the apex of Bronze Age urbanism. Its cultural identity was expressed through remarkable uniformity across its major settlements like Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro, Rakhigarhi, and Dholavira. The inhabitants demonstrated highly developed Art & Craft, excelling in bead-making, the creation of intricate terracotta figurines, and bronze artefacts, including the iconic "Dancing Girl" sculpture and the "Priest-King" bust. This craft specialisation underpinned a robust economy.

The most striking feature was its Architecture & Urban Planning. Cities were laid out on a meticulous grid pattern, with streets intersecting at perfect right angles, dividing the city into rectangular blocks. Houses, predominantly built using standardised baked bricks, featured multi-storey dwellings, private courtyards, and well-developed sanitation systems. Each house had bathrooms connected to an advanced, covered public sewerage and drainage network, an unparalleled feat for its time. Public architecture included large granaries for surplus food storage and ceremonial structures like the Great Bath at Mohenjo-Daro, pointing to an efficient Society & Governance structure dedicated to the collective well-being and management of resources. The economic foundation was diversified, relying heavily on agriculture (wheat, barley, cotton) and sustained by internal trade and long-distance maritime trade with regions like Mesopotamia, Oman, and Iran, evidenced by the ubiquitous seals and standardized weights and measures.

Climate Stress as the Primary Catalyst

The new multi-proxy paleoclimate study delivers the strongest argument yet for a climate-driven decline, fundamentally reshaping the narrative from a sudden collapse to a gradual, complex metamorphosis. This analysis integrates diverse paleoclimate proxies, such as stalagmites from Indian caves, lake cores, and high-resolution hydrological models, to reconstruct ancient water patterns.

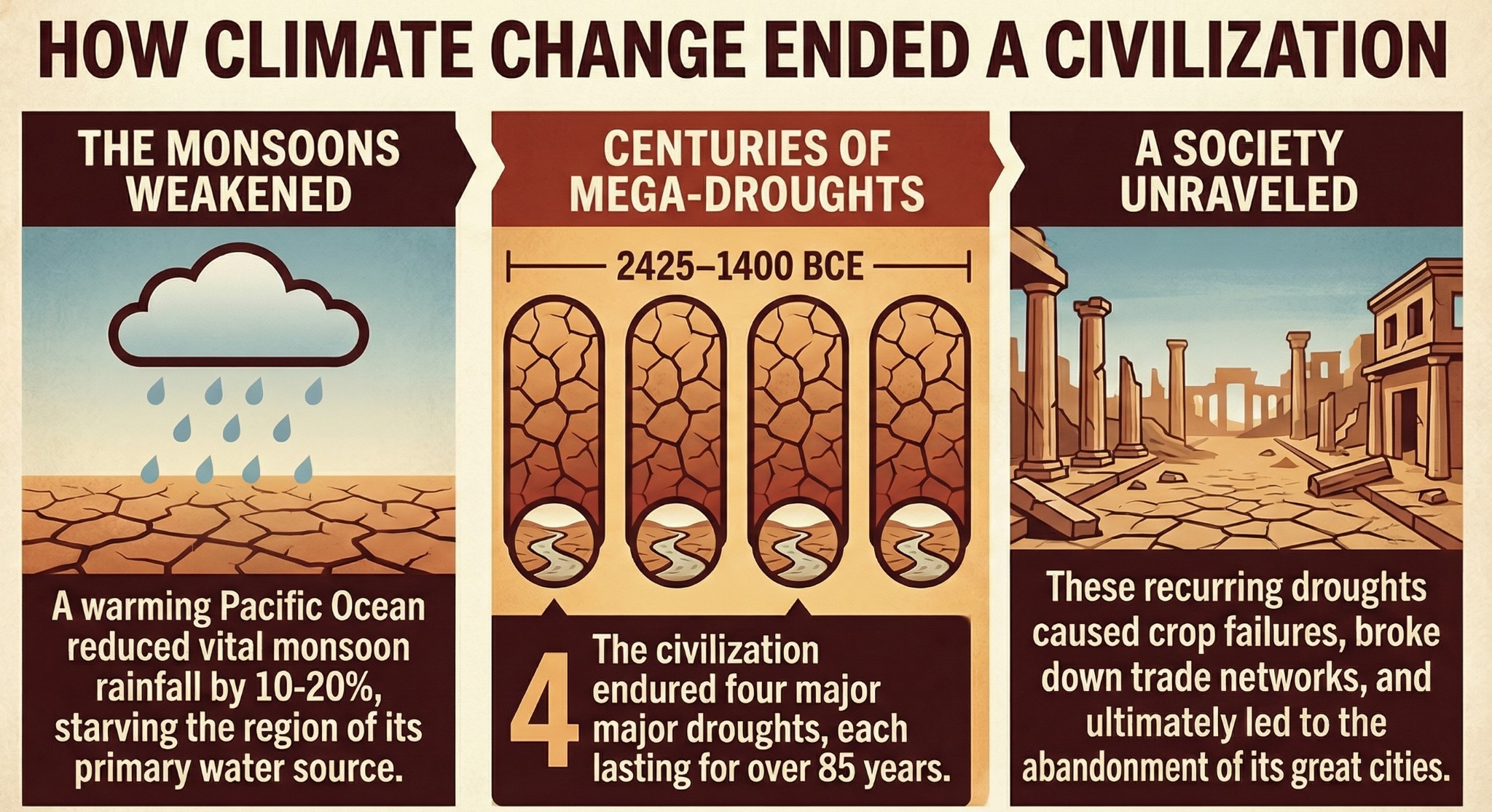

The Role of Recurring Mega-Droughts

The research pinpoints the decline as a protracted, gradual process, primarily triggered by four major, prolonged drought phases that occurred between 2425 and 1400 BCE. These were not isolated dry years but multi-decadal extremes. The study highlights that the most severe of these mega-droughts peaked around 1733 BCE and lasted for approximately 164 years, creating centuries of unrelenting hydrological instability across the region. This sustained aridity systematically undermined the two pillars of Harappan life: monsoon-fed agriculture and riverine trade.

Weakening Monsoons and Aridification

The root cause of these droughts is traced back to large-scale atmospheric shifts. Climate records indicate that the tropical Pacific Ocean began to warm, shifting from a cooler, La Niña-like phase (which historically boosted monsoon intensity) to a warmer, El Niño-like phase. This profound shift directly contributed to the weakening of the Indian Summer Monsoon, leading to a significant 10–20% reduction in average rainfall. This reduced precipitation drastically lowered the water availability for fields, reservoirs, and rivers, intensifying the aridification process across the Harappan plains.

Hydrological Changes and Agricultural Adaptation

The hydrological impact was immediate and destructive. The Ghaggar-Hakra system, once a vital water source (whether perennial or heavily monsoonal-fed is debated), experienced drastically reduced flows and eventual desiccation. Similarly, other rivers and tributaries in the Sutlej-Beas system suffered reduced stream flows. This led to widespread soil desiccation and salinity build-up, making large-scale flood-based agriculture, which relied on the Indus's annual inundation, precarious and eventually impossible.

In response, the Harappans displayed remarkable resilience and agricultural adaptation. Instead of perishing instantly, they were forced to strategically relocate, primarily toward the Indus River itself and, later, eastward toward the Ganga-Yamuna Doab and south toward Gujarat. Critically, their farming strategies changed: they gradually shifted from the traditional, water-intensive winter crops (like wheat and barley, which are examples of Rabi crops) to the more drought-resistant Kharif (summer monsoon) crops, notably millets, rice, and sorghum. While this adaptation sustained life, it weakened the agricultural surplus system that was essential for supporting massive urban centres and specialist crafts.

Fragmentation of Economic Networks

The prolonged environmental stress had a cascading effect on the highly integrated Harappan economy. Lower river levels made river navigation difficult, choking the vital internal waterways used for transporting goods and raw materials. Furthermore, the global trade networks, particularly with Mesopotamia, fractured. As external trade declined, the economic base of urban jobs such as those of bead makers, potters, and metalworkers eroded, leading to the de-urbanisation of major centres. The once-integrated urban civilization fragmented into smaller, more rural settlements known as the Late Harappan cultures.

Re-evaluating Classical Theories

While climate change is now seen as the dominant driver, it did not act in a vacuum. Earlier classical theories contribute to a holistic, multi-factor understanding of the decline.

Changes in River Systems

The drying up of the Ghaggar-Hakra (the likely course of the Vedic Sarasvati River) has long been cited as a major regional factor. New research suggests the Sutlej and Yamuna rivers had already shifted their courses long before the Harappan period. Nonetheless, the continued reliance of many Mature Harappan settlements on this monsoon-fed system meant that the subsequent diminishing monsoons around 4,000 years ago caused the Ghaggar-Hakra system to dry up, forcing the abandonment of major sites like Kalibangan and Banawali. Concurrently, cities on the unstable Indus floodplain, such as Mohenjo-Daro, suffered from recurring, massive tectonic floods that necessitated constant, costly rebuilding, signalling administrative strain.

Trade Collapse and Urban Decay

The Collapse of the Mesopotamian Trade Network around 2000 BCE, linked to internal political turmoil (e.g., the Akkadian collapse), certainly compounded the Harappan decline. This reduction in demand for Harappan luxury goods further destabilised the urban economy. Archaeologically, the concept of Urban Overcrowding and Declining Civic Maintenance is evident: later construction phases show houses built over old streets, clogged drainage systems, and the degradation of monumental structures like the Great Bath. This signifies a weakening of the central civic authority and a deterioration of the high standards of living that had defined the Harappan era.

Crucially, the long-held theory of an "Aryan invasion" causing the sudden destruction of the Harappan civilization has been almost entirely discredited. The archaeological record shows No Evidence of Large-Scale Invasion or Warfare, lacking mass graves, burnt cities, or widespread military paraphernalia. The society appears to have been largely peaceful, and its demise was a slow, socio-environmental collapse, not a military conquest.

Significance and Modern Lessons

The Indus Valley Civilisation’s legacy extends far beyond ancient history. It provided India with its first sophisticated models of planned cities, sanitation systems, and centralized urban governance. The civilization demonstrated advanced water management, craft specialisation, and a remarkable ability to adapt to environmental pressures for almost two millennia.

The contemporary scientific findings demonstrate that the Harappan collapse was not a failure of ingenuity but a slow, climatic tragedy that overwhelmed societal resilience. As the world faces accelerating climate change, the story of the Indus people offers powerful, sobering lessons on climate resilience, water management, and the fragility of densely populated urban centres dependent on stable climate systems. Their eventual shift to millets and decentralised settlement planning underscores the necessity of agricultural diversification and proactive environmental adaptation for the survival of great human cultures.

Conclusion

The new paleoclimate evidence firmly establishes climate change, manifested through multi-century recurring mega-droughts, as the primary, systemic driver of the Indus Valley Civilisation’s demise. This catastrophic environmental pressure fractured its agriculture and economic networks, forcing a gradual but irreversible process of de-urbanisation and migration. The Indus story remains a compelling case study: a complex, resilient society that ultimately succumbed to a confluence of forces, weakening monsoons, regional hydrological changes, and mounting governance stress. It is a powerful reminder that even the most advanced human civilizations are intrinsically linked to the delicate balance of their environment.